Successful project completion in Syria

In the last two years, over 100 orphans who lost their families in the earthquake in Idlib in February 2023 have been rescued in Syria. These children often lived completely on their own in the rubble for weeks, without shelter or help, looking for food in the rubbish and with no roof over their heads. Many of the children were severely traumatised, injured or ill. The project took the children in, had them medically examined and treated. Some of the children had infections that had to be treated with antibiotics, others were so ill that they had to be hospitalised. Almost all of them were severely malnourished and had behavioural problems that indicated trauma. The children also underwent psychological treatment (some still do) to enable them to talk about their experiences and the loss of home, family and identity. The healing of these children is not yet complete, they and the families who took them in still need support, but they are on the right track.

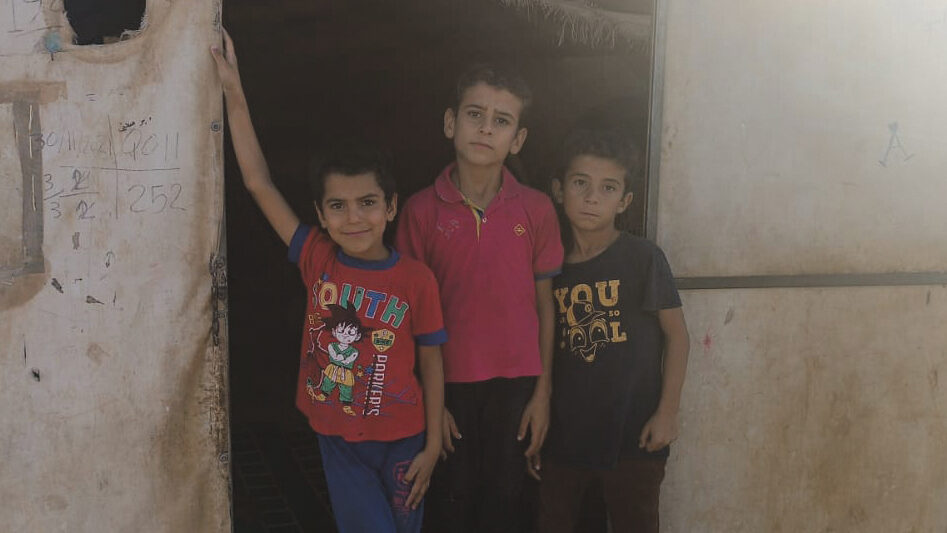

Three of these children are the brothers Esat, Phekda and Aadil, whose story was provided to us by our partner organisation and which we would like to share:

The brothers Esat (10), Phekda and Aadil (twins, both 7) have lost their entire family. Their father died a year ago from rocket fire and they lived with their mother Sama and their one-and-a-half-year-old brother Abdi in the back room of an abandoned bakery, where there was a wood-burning stove but they didn’t use it because they couldn’t afford the wood to light it.

When the earthquake struck, the mother and her little brother were buried in this back room. The three brothers had to watch as their mother died hours later, trapped under the rubble. They took their little brother Abdi to a military hospital, where he was operated on, but the children were then sent home again. In the chaos, no one asked if there was a home, if there were adults to look after them. It is unimaginable how the three boys leave the military hospital with their brother in their arms and have no idea what will happen now and what they should do.

They spent the first night in the ruins of the bakery with their dead mother. But the next morning they were told that the rescue work was still going on and they couldn’t stay here. It may be inconceivable to us that there was no office in charge, no reception centre where they could be cared for, but there was chaos in Idlib, which was already a war zone before the earthquake.

Esat, Phekda, Aadil and Abdi didn’t know where to go. Every night they slept in a different place and during the day they wandered around the ruined city looking for food. Esat remembers that little Abdi cried all the time. ‘We took it in turns to carry him, but he just wouldn’t stop. And it was so cold. And there were constant aftershocks that scared us so much.’ The three older children don’t know whether it was days or weeks that passed like this, but one morning they woke up behind the workshop where they had gone to sleep and it was quiet. Abdi no longer moved. They didn’t speak for minutes, says Phekda, as they each tried to realise that their little brother had died at just 19 months old.

The three brothers buried their little brother Abdi in a field. Three primary school children, all alone, because there was no help in the chaos. ‘Life goes on’ is a phrase that we like to say here in Germany when something bad happens to others and is intended to comfort them. And for Esat, Phekda and Aadil, life simply went on. Without parents. Without a brother. Without a home. There were always people who asked if they no longer had a home when they begged or stole food, but when the boys denied this, when they said they were all alone, there was nothing their counterparts could do. A natural disaster in the middle of a war. Chaos in the middle of a massacre. There was no help.

The first contact was in May, when the boys lined up at a food distribution centre. It was clear to see that they needed far more than bread, juice and cheese. We are therefore delighted to have found a new family for Esat, Phekda and Aadil, where they feel safe and secure. ‘Life goes on”: they wake up every morning in their tent in the peacock camp, where they live with their new parents and two sisters, they eat together with their new family, attend the peacock school, do their homework in the afternoon and slowly, step by step, return to a “normal life”.

Like the three brothers, the peacock camp has given over 100 other children the opportunity to look to the future with optimism and lay the foundations for shaping their future lives. Our partner organisation has provided great help in this particularly challenging environment, built up structures and developed sources of funding so that help alliance financing for the project could be completed at the end of 2024.